How to Fall Asleep Faster: Evidence-Based Techniques for Rapid Sleep Onset

Medical Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Chronic insomnia — difficulty falling or staying asleep occurring at least three nights per week for three months or more — warrants evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is the first-line clinical treatment and is more effective than medication for most people with chronic insomnia. Always consult a healthcare provider before beginning any supplement regimen.

Lying awake with a quiet, dark room and a busy mind is one of the most frustrating experiences in cognitive performance — and one of the most common. The harder you try to fall asleep, the more alert you become. The more you watch the minutes pass, the more sleep pressure transforms into performance anxiety. The brain that is excellent at solving problems turns its attention to the problem of sleep itself, and the attempt produces exactly the opposite of the intended result.

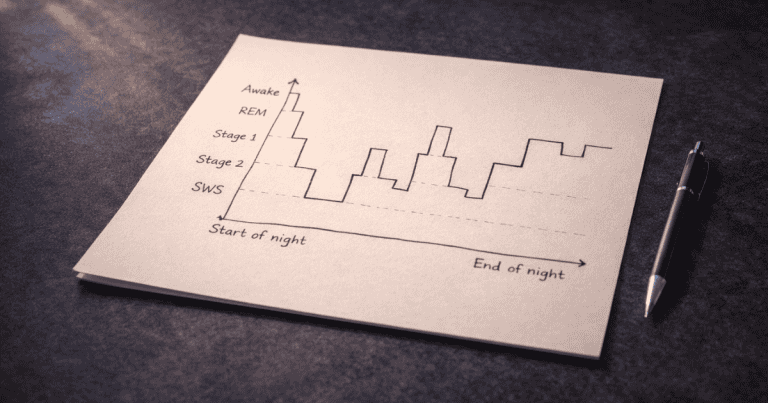

This is not a discipline problem. It is a neurobiological one — and it has neurobiological solutions. Sleep onset is governed by two systems: the adenosine-driven homeostatic sleep pressure that builds across wakefulness and the circadian clock that signals neurochemical sleep conditions at the appropriate time. Difficulty falling asleep almost always involves one of three mechanisms: insufficient sleep pressure at bedtime (caused by late naps, excessive time in bed, or insufficient prior wakefulness), circadian phase mismatch (the biological clock not aligned with the desired sleep time), or hyperarousal (elevated sympathetic nervous system activation, cortisol, or cognitive rumination that prevents the neural transitions sleep onset requires). The intervention that fixes one does not fix the others — and applying the wrong one explains why so many sleep advice recommendations produce no improvement for the specific person trying them.

This guide covers the complete evidence-based protocol for faster sleep onset — organized by mechanism, so you can identify which factor is driving your specific difficulty and apply the interventions that address it directly. It builds on the complete sleep guide and sleep architecture guide, and connects to the supplementation protocols in the Nootropics hub.

The Neuroscience of Sleep Onset: What Has to Happen Before You Can Sleep

Sleep onset is not passive. It requires the coordinated suppression of the arousal systems that maintain wakefulness and the activation of the sleep-promoting systems that initiate the NREM cascade. Understanding this transition makes it clear why effort — trying harder to sleep — is neurobiologically counterproductive.

The Arousal Systems That Must Be Suppressed

Wakefulness is actively maintained by four neurochemical arousal systems: the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (alertness and vigilance), the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (motivational activation), the histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus (waking consciousness), and the cholinergic basal forebrain (cortical arousal and attention). For sleep onset to occur, all four must be progressively suppressed — a process initiated by adenosine accumulation and circadian melatonin signaling acting on the sleep-active ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) of the hypothalamus.

The VLPO is the brain’s sleep switch — when it fires, it inhibits all four arousal systems simultaneously through GABAergic and galaninergic inhibition, producing the coordinated neurochemical shift from wakefulness to sleep. The VLPO is activated by adenosine (the sleep pressure signal), melatonin (the circadian nighttime signal), reduced body temperature, and reduced light input to the SCN. Anything that activates the arousal systems — stress, light, stimulants, cognitive engagement, physical activation — competes with VLPO inhibition and delays or prevents sleep onset.

Why Trying Harder Makes It Worse

The attempt to fall asleep activates the prefrontal cortex’s monitoring and evaluation functions — the same neural systems involved in goal-directed problem solving. PFC activation sustains noradrenergic and cholinergic arousal system activity — directly opposing the VLPO suppression required for sleep onset. This is the neuroscience of sleep-onset performance anxiety: the cognitive effort to achieve sleep neurologically prevents it. Research on cognitive arousal and sleep onset found that pre-sleep cognitive hyperarousal — worry, mental rehearsal, problem-solving — is a stronger predictor of sleep onset latency than physiological arousal measures, and that thought suppression (actively trying not to think) paradoxically increases intrusive thought frequency through the ironic process theory mechanism.

The practical implication is that effective sleep onset interventions must work with the biology rather than through willpower. The goal is not to force sleep but to create the neurochemical conditions — reduced arousal, reduced temperature, reduced light, reduced cortisol, increased adenosine and GABA — that allow the VLPO to do its job without interference.

Diagnosing Your Sleep Onset Problem: Three Mechanisms, Three Solutions

Mechanism 1: Insufficient Sleep Pressure

If you lie down at your target bedtime and feel genuinely not sleepy — no heavy eyelids, no yawning, no gravitational pull toward sleep — the problem may be insufficient adenosine accumulation rather than hyperarousal. This is most common in people who nap late in the day, spend excessive time in bed (including reading, scrolling, or lying awake), or have irregular sleep schedules that fragment adenosine accumulation across inconsistent wake periods.

Solution: Sleep restriction and stimulus control. The clinical CBT-I technique for insufficient sleep pressure is temporarily restricting time in bed to match actual sleep time — which concentrates adenosine accumulation and intensifies sleep pressure at the target bedtime. If you are sleeping 5 hours despite being in bed for 8, restricting time in bed to 5.5 hours builds the sleep pressure that makes falling asleep faster unavoidable, then gradually extending from that foundation. Stimulus control — using the bed only for sleep (not reading, scrolling, working) — trains the brain’s associative learning to treat bed as a sleep cue rather than a wakefulness-compatible environment. Within 1–2 weeks, the conditioned association between bed and sleep onset restores the rapid sleep onset that most people experienced effortlessly as children.

Mechanism 2: Circadian Phase Mismatch

If you feel tired throughout the evening but then experience a “second wind” — sudden alertness — near your target bedtime, the problem is likely circadian phase delay: your biological clock is scheduled for sleep later than your desired bedtime. This is extremely common in individuals who use screens late into the evening, have irregular light exposure patterns, or have a natural chronotype that runs late.

Solution: Circadian phase advancement. Morning bright light exposure (10–20 minutes outdoors within 30–60 minutes of waking) is the most powerful circadian phase-advancing intervention available — it shifts the biological clock earlier, moving the natural sleep onset time progressively earlier by 15–30 minutes per day of consistent application. Evening light restriction — dim, warm-toned lighting after 9pm, blue-light-blocking glasses for screen use, complete light elimination in the bedroom — prevents the phase-delaying light that counteracts morning advancement. Low-dose melatonin (0.5mg, not 5mg) taken 5–6 hours before the target bedtime acts as a circadian phase-advancing signal — distinct from melatonin’s use as a sedative, which is pharmacologically ineffective at any dose. Research on low-dose melatonin and circadian phase advancing found that 0.5mg is as effective as higher doses for phase shifting while producing fewer next-day side effects.

Mechanism 3: Hyperarousal

If you feel tired, lie down at an appropriate time, but find your mind racing — replaying the day, planning tomorrow, unable to stop thinking — the problem is hyperarousal: elevated sympathetic nervous system activity, cortisol, or cognitive activation that prevents the VLPO from suppressing arousal systems. This is the most common sleep onset mechanism in cognitively active adults, and it is the mechanism that behavioral sleep techniques most directly address.

The hyperarousal mechanism requires specific interventions: the sections below cover the complete evidence-based toolkit for this mechanism, which most people experiencing sleep onset difficulty will recognize as their primary problem.

The Evidence-Based Hyperarousal Toolkit: Faster Sleep Through Neuroscience

The 4-7-8 Breathing Technique: Activating the Parasympathetic Brake

Controlled breathing is the most direct voluntary intervention on the autonomic nervous system available — and the 4-7-8 pattern (inhale for 4 counts, hold for 7, exhale for 8) is the most evidence-supported controlled breathing protocol for pre-sleep parasympathetic activation. The extended exhale — twice the length of the inhale — activates the baroreflex arc that increases vagal tone, directly suppressing sympathetic nervous system activity and reducing noradrenergic arousal. Research on slow breathing and autonomic function found that slow, diaphragmatic breathing with extended exhalation significantly increases heart rate variability (the physiological marker of parasympathetic dominance) and reduces cortisol — two direct inputs to the VLPO activation that initiates sleep onset. Three to four cycles of 4-7-8 breathing in bed, with attention on the breath sensation rather than on thought content, reliably reduces time to sleep onset in hyperarousal-driven insomnia.

The Cognitive Shuffle: Disrupting the Narrative Mind

Cognitive hyperarousal at sleep onset is characterized by narrative, sequential thought — the story of tomorrow’s meeting, the replay of today’s difficult conversation, the mental to-do list. Narrative thought requires the prefrontal cortex and default mode network, whose activation maintains arousal system activity. Disrupting narrative thought — replacing sequential, meaningful cognitive content with random, disconnected imagery — allows the arousal systems to quiet without requiring the thought suppression that paradoxically intensifies them.

The cognitive shuffle technique, developed based on research on hypnagogic (sleep-onset) cognition, involves generating a random word and then visualizing a series of unrelated images associated with it — nonsensical, disconnected, non-narrative imagery that cannot build the sequential story structure that narrative thought requires. For example: “umbrella” → a purple umbrella floating over a desert → a cartoon ostrich holding the umbrella → the ostrich eating a sandwich → a bicycle made of sandwiches. The absurdity is functional — it prevents the mind from constructing the meaningful narrative sequences that sustain prefrontal activation. Research on imagery and sleep onset found that distraction imagery significantly reduced sleep onset latency compared to counting sheep or unguided thought — the random, disconnected nature of the imagery is the active mechanism.

The Written Worry Discharge: Closing Mental Open Loops

One of the most replicated findings in sleep onset research is that cognitive arousal from unresolved mental tasks — open loops, unprocessed concerns, incomplete planning — sustains prefrontal activation at bedtime because the brain continues processing unfinished business during the transition to sleep. Research by Scullin and colleagues found that writing a specific to-do list — not a worry journal, but a concrete list of tomorrow’s tasks — for five minutes before bed significantly reduced sleep onset latency. The mechanism is the transfer of open loop processing from working memory to external storage, which allows the prefrontal monitoring systems to disengage from active maintenance of those representations.

The practical protocol: 5–10 minutes of paper journaling (not phone) 30–60 minutes before bed — writing tomorrow’s concrete task list, closing any significant open concerns by noting the next action, and briefly noting the day’s one or two most important completed items. This is not emotional processing or gratitude journaling — it is specifically the task-level, concrete next-action writing that discharges the working memory maintenance function that sustains pre-sleep arousal.

Free Download

Get the 7-Day Brain Optimization Protocol

The evidence-based diet, sleep, and supplement framework for your first week of cognitive enhancement — completely free.

Join 2,000+ readers optimizing their cognitive performance. Unsubscribe anytime.

Body Scan Progressive Relaxation: Bottom-Up Arousal Reduction

Progressive muscle relaxation — the systematic tensing and releasing of muscle groups from feet to head — and its lighter variation, body scan awareness, reduce sleep onset latency through bottom-up somatic pathways that bypass the cognitive hyperarousal loop. Muscle relaxation activates the proprioceptive relaxation response that reduces sympathetic tone through peripheral nervous system feedback — the body signaling the brain that the threat requiring arousal has passed, rather than the mind trying to convince the arousal systems to quiet through top-down effort.

Research on progressive muscle relaxation and sleep onset found significant reductions in sleep onset latency in both clinical insomnia populations and healthy poor sleepers. The mechanism differs from breathing techniques (which work top-down through voluntary autonomic regulation) — PMR works bottom-up through peripheral muscle relaxation feedback. The two techniques are complementary: 4-7-8 breathing first (2 minutes, autonomic regulation), followed by body scan PMR (5–10 minutes, somatic relaxation) produces the most comprehensive pre-sleep arousal reduction available without supplementation.

The Supplementation Layer: L-Theanine and Ashwagandha

For individuals whose hyperarousal has a chronic stress component — elevated baseline cortisol, persistent sympathetic tone that behavioral techniques alone cannot fully resolve — supplementation directly addresses the neurochemical substrate of hyperarousal.

L-theanine at 200–400mg taken 45–60 minutes before bed promotes alpha-wave brain activity — the same relaxed, non-drowsy mental state that characterizes mindfulness practice — through GABA enhancement and glutamate inhibition. Unlike sedatives, L-theanine does not produce grogginess or impair next-day alertness — it specifically reduces the cognitive hyperarousal of a busy mind without sedation. In my own testing, L-theanine is the most reliably effective single intervention for the racing-mind type of sleep onset difficulty — producing the subjective experience of thoughts slowing and becoming less compelling without the cognitive suppression that creates rebound effect.

Ashwagandha KSM-66 at 300–600mg in the evening addresses the chronic HPA axis dysregulation that produces persistently elevated evening cortisol. Research on Ashwagandha and sleep onset found significant reductions in sleep onset latency in stressed adults after 8 weeks of supplementation — with the mechanism clearly tied to cortisol reduction and HPA axis normalization rather than direct sedation. This makes Ashwagandha the appropriate choice when sleep onset difficulty is part of a broader stress and anxiety pattern rather than isolated pre-sleep hyperarousal. See the full protocol in the Ashwagandha guide.

The Complete Sleep Onset Protocol: Integrated Timing

The complete protocol addresses all three mechanisms simultaneously — which is appropriate because most people have some contribution from each.

During the day: Consistent wake time every morning (anchors circadian clock). Morning light within 60 minutes of waking (circadian phase advancement). No naps after 2pm, no naps longer than 20 minutes (preserves adenosine sleep pressure). Caffeine cutoff by noon (preserves adenosine receptor availability at bedtime).

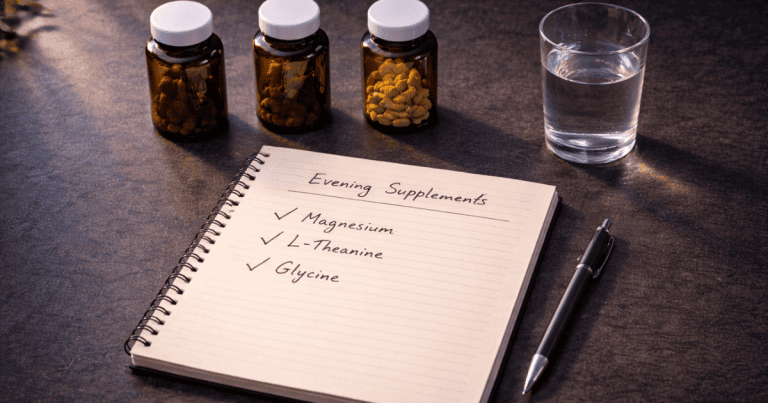

90 minutes before target bedtime: Dim all lights to warm, low-level illumination or put on blue-light-blocking glasses. Take L-theanine 200–400mg + Ashwagandha 300–600mg + Magnesium L-Threonate evening dose. Warm shower or bath (core temperature drop initiation). Set bedroom to 65–68°F.

30–60 minutes before bed: Paper journaling — 5–10 minutes of tomorrow’s concrete task list and open loop closure. Brief active recall review of the day’s learning (10 minutes). Light reading in dim light or quiet conversation. No screens without blue-light-blocking glasses. No work-related cognitive engagement.

In bed: Complete light elimination — blackout curtains or sleep mask. 2–3 minutes of 4-7-8 breathing. Body scan progressive relaxation from feet to head. If thoughts arise, cognitive shuffle — generate a random word and follow the disconnected imagery chain without narrative. If not asleep within 20 minutes, leave the bed and engage in quiet, non-stimulating activity until sleepy, then return (stimulus control).

Frequently Asked Questions About Falling Asleep Faster

How can I fall asleep faster when my mind won’t stop racing?

Racing mind at sleep onset is cognitive hyperarousal — the prefrontal cortex and default mode network sustaining narrative thought that prevents the VLPO suppression of arousal systems that sleep onset requires. The most effective interventions work by disrupting or redirecting the narrative thought rather than suppressing it (thought suppression paradoxically increases intrusive thought frequency). The cognitive shuffle technique — generating a random word and visualizing a series of disconnected, nonsensical images — is specifically designed to prevent the sequential narrative structure that sustains pre-sleep cognitive activation. Paired with 4-7-8 breathing (4 count inhale, 7 hold, 8 exhale) to activate parasympathetic tone, and 5–10 minutes of paper to-do list writing 30–60 minutes before bed to discharge working memory open loops, this three-component approach addresses hyperarousal from multiple angles simultaneously. L-theanine at 200–400mg taken 45–60 minutes before bed directly reduces cognitive hyperarousal through alpha-wave promotion without sedation. For persistent hyperarousal with a chronic stress component, Ashwagandha KSM-66 at 300–600mg evening dose addresses the cortisol elevation that sustains sympathetic arousal.

What is the fastest way to fall asleep?

The fastest sleep onset occurs when all the necessary neurobiological conditions are simultaneously met: sufficient adenosine sleep pressure from adequate prior wakefulness, circadian alignment between biological clock and target sleep time, reduced core body temperature, eliminated light input, and suppressed sympathetic nervous system arousal. For immediate application tonight, the most impactful single intervention is the temperature protocol — taking a warm shower 60–90 minutes before bed to accelerate core temperature drop, combined with setting the bedroom to 65–68°F. Adding 4-7-8 breathing once in bed (three to four cycles) and complete light elimination produces the three primary conditions for rapid VLPO activation. For individuals with hyperarousal, L-theanine 200–400mg taken 45–60 minutes before bed provides an additional direct reduction in cognitive arousal. Combining all four — temperature protocol, light elimination, breathing technique, and L-theanine — represents the most evidence-supported acute sleep onset optimization available without prescription medication.

Does melatonin help you fall asleep faster?

Melatonin’s effect on sleep onset depends entirely on which mechanism is causing the delay. Melatonin is a circadian timing signal — it advances the circadian clock when taken at the right time and dose, making sleep onset feel appropriate at an earlier target time. If circadian phase delay is the cause of your sleep onset difficulty (you feel a “second wind” near your desired bedtime, you naturally feel sleepy much later than desired), low-dose melatonin (0.5mg, not 5–10mg) taken 5–6 hours before target bedtime is an effective phase-advancing intervention. If the cause is hyperarousal or insufficient sleep pressure rather than circadian misalignment, melatonin is not effective — it is not a sedative and does not directly suppress arousal systems. The common use of high-dose melatonin (5–10mg) at bedtime as a sleep aid is pharmacologically misguided — it produces supraphysiological melatonin levels that can desensitize receptors and shift circadian timing without proportionally improving sleep quality.

Why do I fall asleep on the couch but then can’t sleep in bed?

This is a classic presentation of conditioned arousal — the bed has been associated with wakefulness through repeated experiences of lying awake in it, while the couch remains a neutral stimulus without this conditioning. The brain’s associative learning system links the bed with the vigilance and frustration of previous sleepless nights, producing a conditioned arousal response whenever you enter the bed environment — the opposite of what is needed for sleep. The stimulus control intervention addresses this directly: use the bed only for sleep (and sex), never for reading, watching TV, scrolling, or working. If you are not asleep within 20 minutes in bed, leave the bed and sit quietly on the couch until genuinely sleepy, then return. Over 1–3 weeks of consistent application, this breaks the conditioned arousal association and rebuilds the bed-sleep association that allows rapid sleep onset in bed. The couch sleepiness is a feature of this reconditioning process — it shows that your sleep drive is intact and the problem is location-specific conditioning rather than physiological inability to sleep.

How long should it take to fall asleep?

Sleep onset latency — the time from lights out to the first epoch of sleep — is considered normal within a range of 10–20 minutes. Less than 5 minutes suggests significant sleep deprivation (the brain is not sleepy within seconds of lying down under normal conditions — this rapid onset indicates insufficient sleep). More than 30 minutes on a consistent basis suggests sleep onset difficulty, the mechanism of which this guide is designed to diagnose and address. The occasional night of longer sleep onset — after a stressful event, travel across time zones, unusual schedule disruption — is normal and not a sleep disorder. The clinical threshold for insomnia disorder is sleep onset taking more than 30 minutes at least three nights per week for at least three months, significantly affecting daytime functioning. Individuals meeting this threshold should consult a healthcare provider for evaluation and possible CBT-I referral — the behavioral interventions in this guide are consistent with CBT-I principles but do not substitute for professional evaluation of persistent clinical-level insomnia.

Sleep Onset as a Skill, Not a State

The reframe that makes the difference: falling asleep is not something that happens to you when you are tired enough. It is a neurobiological transition that requires specific conditions — conditions that can be deliberately created through behavioral and neurochemical interventions that are now well-understood. The reason sleep onset feels effortless in childhood and progressively more effortful in cognitively active adulthood is not aging — it is the accumulation of conditioned arousal, circadian disruption from artificial light, and the hyperarousal that comes with carrying the cognitive load of adult responsibility into the sleep environment without a deliberate discharge protocol.

The interventions in this guide — the temperature protocol, light management, breathing technique, cognitive shuffle, written to-do discharge, stimulus control, L-theanine, and Ashwagandha — collectively address every mechanism through which sleep onset is delayed. Applied as a complete protocol for 2–3 weeks, most people experience sleep onset times under 15 minutes that were previously closer to 45–60, without pharmacological sedation and without the next-day impairments that sedating drugs and high-dose melatonin produce.

For the deeper sleep quality that fast sleep onset initiates, see the complete sleep guide. For the supplement details on L-theanine and Ashwagandha, see the Ashwagandha guide in the Nootropics hub. For how the sleep that follows affects memory and cognitive performance, see the sleep and memory guide.

References

- Harvey, A.G. (2002). A cognitive model of insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 869–893. PubMed

- Leproult, R., et al. (1997). Transition from dim to bright light in the morning induces an immediate elevation of cortisol levels. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(11), 3649–3654. PubMed

- Zaccaro, A., et al. (2018). How breath-control can change your life: A systematic review on psycho-physiological correlates of slow breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 353. PubMed

- Scullin, M.K., et al. (2018). The effects of bedtime writing on difficulty falling asleep: A polysomnographic study comparing to-do lists and completed activity lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(1), 139–146. PubMed

- Baddeley, M., et al. (2019). Imagery distraction and sleep onset latency. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 120, 103437. PubMed

- Lauche, R., et al. (2014). Progressive muscle relaxation for insomnia: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18(4), 325–335. PubMed

- Langade, D., et al. (2019). Efficacy and safety of Ashwagandha root extract in insomnia and anxiety. Cureus, 11(9), e5797. PubMed

- Rao, T.P., et al. (2015). In search of a safe natural sleep aid: L-theanine. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 34(4), 436–447. PubMed

- Morin, C.M., et al. (2006). Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia. Sleep, 29(11), 1398–1414. PubMed

Tags: how to fall asleep faster, sleep onset, fall asleep quickly, hyperarousal insomnia, cognitive shuffle sleep, 4-7-8 breathing sleep, progressive muscle relaxation sleep, L-theanine sleep onset, sleep onset latency, circadian phase delay sleep, stimulus control insomnia, VLPO sleep switch, adenosine sleep pressure, to-do list sleep, Ashwagandha sleep onset

About Peter Benson

Peter Benson is a cognitive enhancement researcher and mindfulness coach with 18+ years of personal and professional experience in nootropics, neuroplasticity, and sleep optimization protocols. He has personally coached hundreds of individuals through integrated cognitive performance programs combining evidence-based sleep strategies with targeted supplementation. NeuroEdge Formula is his platform for sharing rigorous, safety-first cognitive enhancement guidance.