Sleep Architecture: Understanding Sleep Stages and Cycles

Medical Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Sleep disorders require professional evaluation. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before beginning any supplement regimen or if you have concerns about your sleep health. Individual responses vary.

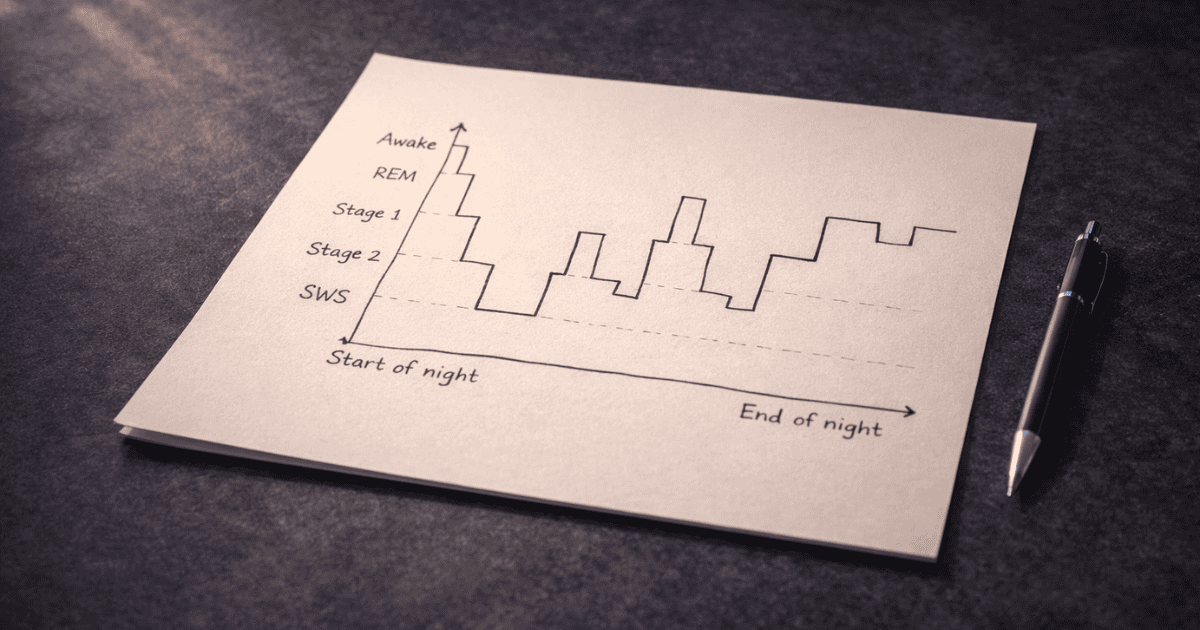

Most people think of sleep as a single uniform state — you close your eyes, unconsciousness happens, you wake up. The reality is that sleep is one of the most architecturally complex processes the brain performs: a precisely orchestrated sequence of neurologically distinct states cycling through a predictable pattern across the night, each stage serving specific biological functions that no other stage replicates. Understanding this architecture is not merely academic — it is the practical foundation for every sleep optimization decision, because different interventions affect different stages, and the impairments that disrupt cognitive performance, physical recovery, and memory consolidation are stage-specific.

When someone says their sleep is poor, the useful question is not “how many hours?” but “which stages are being disrupted and why?” A person sleeping 8 hours with alcohol-suppressed REM has a fundamentally different sleep problem than someone sleeping 6 hours with truncated slow-wave sleep from a too-warm bedroom. The intervention that fixes one does nothing for the other. Sleep architecture gives the diagnostic framework that makes optimization precise.

This guide covers the complete neuroscience of sleep architecture — what happens in each stage at the neurological level, how stages cycle across the night and why that pattern matters, how aging and lifestyle factors alter sleep architecture, and what specific disruptions produce which specific cognitive and physical consequences. It builds on the foundations in the complete sleep guide and connects to the sleep and memory consolidation guide and the Sleep hub’s supplementation protocols.

The Four Stages of Sleep: What the Brain Is Actually Doing

Sleep stages are defined by their characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns — the electrical signatures of synchronized neural activity that distinguish each stage from every other. These are not arbitrary classifications but neurologically meaningful states with distinct neurotransmitter profiles, physiological functions, and vulnerability to specific disruptions.

NREM Stage 1 (N1): The Sleep Threshold

N1 is the hypnagogic transition between wakefulness and sleep — lasting 1–7 minutes and characterized by the replacement of waking alpha waves (8–13 Hz, relaxed but alert) with slower theta waves (4–8 Hz). During N1, the thalamus begins withdrawing the sensory relay function that keeps waking consciousness connected to the environment — the characteristic experience of sounds becoming more distant and less meaningful, and the hypnic jerks that occur when the motor system briefly interprets the relaxing muscle tone as a fall.

N1 accounts for approximately 5% of total sleep time and produces no meaningful restorative benefit — it is the neurological gateway to deeper sleep rather than a substantively productive sleep state. Individuals who spend excessive time in N1 — due to hyperarousal, anxiety, or environmental disruption — have reduced total time available for the restorative stages and experience subjectively poor sleep quality even when total time in bed is adequate.

NREM Stage 2 (N2): The Sleep Backbone

N2 is the dominant sleep stage by duration — accounting for approximately 45–55% of total sleep time in healthy adults. Its defining EEG features are sleep spindles and K-complexes, each serving distinct neurobiological functions.

Sleep spindles — bursts of 12–15 Hz thalamo-cortical oscillatory activity lasting 0.5–2 seconds — are generated by the thalamic reticular nucleus and represent one of the most important functional elements of sleep. Research on sleep spindles and cognitive function found that sleep spindle density correlates with fluid intelligence, processing speed, and memory consolidation — making N2 sleep quality a direct cognitive performance variable rather than merely a transitional stage between more important states. Sleep spindles actively suppress external sensory arousal — preventing environmental sounds from waking the sleeper while deep consolidation processes operate — and coordinate the hippocampal memory replay that transfers newly encoded memories into cortical long-term storage.

K-complexes — large-amplitude biphasic slow waves of 0.5–1 Hz lasting at least 0.5 seconds — represent a different function: the detection and suppression of potentially arousing stimuli. When a sleeping person is exposed to a sudden noise, a K-complex fires — representing the brain’s decision that the stimulus does not require awakening. K-complex density reflects the arousal threshold of sleep — higher K-complex rates indicate more robust sleep maintenance against environmental disruption.

NREM Stage 3 (N3): Slow Wave Sleep — The Deep Restoration Engine

N3, or slow wave sleep (SWS), is the most physiologically and cognitively restorative sleep stage — characterized by high-amplitude, low-frequency delta waves (0.5–4 Hz) comprising at least 20% of EEG activity. During SWS, the brain operates in a fundamentally different mode from wakefulness: the thalamus fully withdraws sensory relay, cortical neurons oscillate in synchronized slow waves of activity followed by near-silence, and the biological restoration processes that define sleep’s unique functions operate at peak intensity.

Growth hormone secretion: Approximately 70–80% of the day’s growth hormone is secreted in a single large pulse during the first SWS episode of the night. Growth hormone is not merely a muscle growth signal — it is the primary anabolic hormone for cellular repair, protein synthesis, immune cell production, and metabolic regulation throughout the body. Research on SWS and growth hormone secretion found that growth hormone release is tightly coupled to SWS depth — deeper SWS produces larger growth hormone pulses, while SWS suppression from alcohol, poor sleep hygiene, or sleep disorders directly reduces growth hormone secretion and its associated restoration processes.

Glymphatic clearance: The brain’s waste clearance system — the glymphatic network — is approximately 10 times more active during SWS than during wakefulness. Research by Xie and colleagues found that during SWS, interstitial space in the brain expands by approximately 60%, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to flow through and flush out metabolic waste products including amyloid-beta and tau — the proteins that accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease when chronic SWS impairment reduces glymphatic function over years and decades. SWS quality is therefore simultaneously a next-day cognitive performance variable and a decades-long brain health variable.

Declarative memory consolidation: The hippocampal sharp-wave ripple replay of encoded memories — coordinated with sleep spindles through thalamic timing — occurs primarily during SWS. Each slow oscillation up-state triggers spindle-coupled hippocampal replay events, progressively transferring hippocampal memory traces into distributed neocortical networks for long-term storage. This is covered in depth in the sleep and memory guide.

REM Sleep: The Brain’s Integration Laboratory

REM sleep is the neurologically most paradoxical sleep stage — characterized by EEG activity nearly identical to wakefulness, near-complete skeletal muscle atonia (preventing the physical enactment of dreams), rapid conjugate eye movements, and the vivid narrative experiences of dreaming. Research on REM sleep functions has established four primary roles that are not replicated by any other sleep stage.

Emotional memory processing: REM sleep replays emotionally charged memories in a neurochemical environment low in norepinephrine — the primary stress neuromodulator — allowing the emotional intensity of experiences to be reduced while their informational content is preserved. This is the neuroscience of “sleeping on it” — the well-documented phenomenon of emotional regulation improving after REM-rich sleep, and the mechanism by which PTSD is worsened by REM-suppressing medications and alcohol.

Creative integration: The low-norepinephrine, high-acetylcholine neurochemical environment of REM sleep produces loose associative cognitive processing — reducing the top-down prefrontal control that normally suppresses unexpected connections between distantly related memories. This produces the creative insights, novel associations, and problem solutions that frequently arrive on waking from REM-rich sleep. Research has demonstrated that REM sleep specifically enhances the discovery of hidden relational rules embedded in previously learned material — producing insight that waking analysis of the same material fails to achieve.

Procedural and motor memory consolidation: While declarative memory consolidation is primarily a SWS function, procedural and motor skills — the implicit memories of how to perform physical and cognitive tasks — are consolidated primarily during REM sleep. Musicians, athletes, and anyone developing complex motor or procedural skills benefit specifically from adequate REM cycling.

Synaptic homeostasis: REM sleep contributes to synaptic downscaling — the pruning of weak, redundant synaptic connections that accumulates during waking learning. This downscaling is essential for signal-to-noise optimization: the brain must remove weak connections to maintain the clarity of the stronger, more meaningful ones. Chronic REM deprivation gradually degrades this optimization, producing the cognitive “haziness” associated with accumulated sleep debt.

The Sleep Cycle: How Architecture Changes Across the Night

Sleep does not cycle through stages randomly — the proportion of each stage within each cycle follows a systematic pattern across the night that has profound implications for what happens when sleep is shortened or disrupted at different points.

The 90-Minute Cycle and Its Night-to-Night Variation

Each sleep cycle lasts approximately 90 minutes (ranging from 70 to 110 minutes across individuals), and a full night’s sleep typically contains 4–6 complete cycles. The stage composition of each cycle changes systematically: early cycles (cycles 1–2) are SWS-dominant, containing the longest and deepest slow wave sleep episodes of the night. Later cycles (cycles 4–6) are REM-dominant, containing progressively longer REM episodes while SWS becomes minimal or absent.

This architecture reflects the biological priority system for sleep functions: the body front-loads the physically most critical restoration (SWS, growth hormone, glymphatic clearance) early in the night when sleep pressure is highest and most reliable, then devotes the lower-pressure second half of the night to the cognitive and emotional integration functions of REM. The practical consequence is that the two halves of the night are not interchangeable — the first half provides SWS-dependent physical restoration and declarative memory consolidation that cannot be recovered by additional sleep later; the second half provides REM-dependent cognitive integration and emotional processing that cannot be recovered by additional SWS earlier.

The Critical Asymmetry: Why Truncated Sleep Costs More Than It Seems

Research on sleep stage distribution across the night quantified the asymmetry: while SWS is concentrated in the first 3–4 hours, REM sleep constitutes approximately 20–25% of total sleep time in a full 8-hour night but drops to less than 10% in a 6-hour night — because the truncated night eliminates the REM-dominant later cycles disproportionately. Someone sleeping 6 hours instead of 8 does not lose 25% of their REM — they lose approximately 60–70% of their total REM sleep for the night.

This asymmetry explains why chronic mild sleep restriction produces such severe cognitive consequences disproportionate to the apparently modest reduction in sleep time. It also explains the characteristic profile of sleep-restricted cognition: emotional dysregulation, reduced creativity, impaired procedural skill execution, and the accumulation of unprocessed emotional experiences — all REM-dependent functions that 6-hour sleepers progressively lose access to.

Free Download

Get the 7-Day Brain Optimization Protocol

The evidence-based diet, sleep, and supplement framework for your first week of cognitive enhancement — completely free.

Join 2,000+ readers optimizing their cognitive performance. Unsubscribe anytime.

What Disrupts Sleep Architecture — and the Specific Consequences

Understanding sleep architecture makes the consequences of common sleep disruptors specific and actionable — each disruptor has a characteristic stage-specific signature that explains the pattern of impairment it produces.

Alcohol: SWS Rebound and REM Suppression

Alcohol produces a characteristic two-phase disruption of sleep architecture. In the first half of the night, alcohol’s GABAergic sedation deepens N2 and produces a modest SWS rebound — which is the mechanism behind the subjective impression that alcohol helps you sleep. In the second half of the night, as alcohol is metabolized, the GABAergic suppression reverses into neurological rebound activation: REM sleep is severely suppressed, sleep becomes fragmented, and arousal frequency increases. The net result across the full night is reduced total REM, increased N1 and wakefulness, and a sleep architecture that produces the characteristic next-day emotional reactivity, reduced creativity, and cognitive fatigue of REM-deprived sleep — regardless of total sleep duration.

Caffeine: SWS Reduction Without Perceived Sleepiness

Caffeine consumed in the afternoon reduces SWS duration and depth even when sleep onset is not noticeably delayed — because adenosine receptor blockade reduces the sleep pressure that normally drives SWS intensity, without producing sufficient subjective sleepiness to indicate a problem. The result is a night of sleep that feels normal but contains shallower, less physically restorative SWS — with consequences for growth hormone secretion, glymphatic clearance, and declarative memory consolidation that accumulate across days of habitual afternoon caffeine use.

Blue Light in the Evening: Circadian Delay and SWS Timing Shift

Evening light exposure — particularly the short-wavelength blue light from screens — suppresses melatonin production and delays the circadian clock’s sleep-onset signal. This produces a characteristic shift in sleep architecture: because sleep onset is delayed while the wake time may remain fixed, the night’s SWS episodes begin later and may be cut off by the alarm before completing — reducing total SWS time without the person recognizing that their evening light exposure is the cause. The circadian delay from evening light is cumulative across nights, producing a progressively later sleep phase that increasingly conflicts with fixed wake obligations.

Aging: The Natural SWS Decline

Research on sleep architecture across the lifespan found that SWS declines dramatically with age — from approximately 20% of sleep time in young adults to less than 5% in adults over 60 — with the most significant decline occurring between the 30s and 50s. This age-related SWS reduction is not merely an inconvenience but a significant contributor to age-related cognitive decline, reduced immune function, metabolic disruption, and the accumulation of amyloid-beta from reduced glymphatic clearance. The sleep optimization interventions — consistent timing, temperature, light management, MgT for sleep spindle support — are particularly impactful for older adults precisely because they target the SWS mechanisms that aging most compromises.

Stress and Cortisol: Fragmented Architecture Throughout

Elevated cortisol from chronic stress produces architecture-wide disruption: reduced SWS depth (cortisol activates the HPA axis during sleep, counteracting the SWS-deepening processes), increased sleep fragmentation (elevated sympathetic tone lowers the arousal threshold across all stages), and reduced REM duration (cortisol’s arousal effects preferentially disrupt the lighter, more arousable REM episodes). The result is a sleep architecture that looks superficially normal by duration but is functionally impaired across every restorative function — the neuroscience of why chronically stressed individuals consistently report feeling unrefreshed even after long sleep.

Optimizing Sleep Architecture: Stage-Specific Interventions

Understanding which stage is being disrupted is what makes sleep optimization targeted rather than generic. The following maps the evidence-based interventions to their stage-specific effects.

For SWS depth and duration: Bedroom temperature at 65–68°F (the temperature drop drives SWS); Magnesium L-Threonate at 1,500–2,000mg daily with evening dose 1–2 hours before bed (GABAergic and NMDA support for SWS induction and sleep spindle density); consistent sleep timing (circadian SWS scheduling); caffeine cutoff by noon (preserving adenosine sleep pressure for SWS intensity); morning exercise (BDNF elevation supports SWS architecture); Ashwagandha for cortisol management (removing the primary SWS disruptor in stressed individuals).

For REM protection: Adequate total sleep duration — 7–9 hours — to reach the REM-dominant late cycles; complete alcohol avoidance within 4 hours of sleep (the most impactful single REM protection intervention); stress management for cortisol reduction; consistent sleep timing to complete the full cycle architecture without truncation.

For sleep spindle quality (N2 cognitive function): Magnesium L-Threonate has the most direct evidence for sleep spindle density enhancement; consistent sleep timing and circadian entrainment maintain the thalamo-cortical oscillatory system that generates spindles; Ashwagandha’s cortisol reduction protects the arousal threshold that spindle generation requires.

For sleep onset (N1 to N2 transition speed): L-theanine 200–400mg 45–60 minutes before bed (alpha-wave promotion reducing cognitive hyperarousal); the pre-bed warm shower (temperature drop accelerating sleep onset); light elimination; and the stimulus control principle of leaving the bed if sleep onset takes more than 20 minutes.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sleep Architecture

What is sleep architecture and why does it matter?

Sleep architecture is the pattern and proportion of sleep stages — N1, N2, N3 (slow wave sleep), and REM — that occur across a sleep period. It matters because each stage serves distinct biological functions that cannot be performed by other stages: SWS provides physical restoration through growth hormone secretion, glymphatic brain waste clearance, and declarative memory consolidation; REM provides emotional processing, creative integration, and procedural memory consolidation; N2 provides the sleep spindle-mediated cognitive maintenance and sensory suppression that protect deeper sleep. The architecture is not uniform across the night — SWS dominates early cycles while REM dominates later ones — and different disruptors (alcohol, caffeine, stress, aging) produce characteristic stage-specific impairments. Understanding which stage is disrupted is what makes sleep optimization precise: the intervention that improves SWS (temperature reduction, MgT) differs from the one that protects REM (alcohol avoidance, adequate sleep duration), and applying the wrong intervention to the wrong problem produces no improvement.

How can I get more deep sleep (slow wave sleep)?

Slow wave sleep depth and duration are primarily determined by sleep pressure (adenosine accumulation), body temperature dynamics, cortisol levels, and neurochemical support for the thalamo-cortical oscillations that generate SWS. The most evidence-supported interventions for increasing SWS are: bedroom temperature at 65–68°F to optimize the thermal gradient required for deep SWS induction; caffeine cutoff by noon to preserve the adenosine sleep pressure that drives SWS intensity; alcohol avoidance within 4 hours of bed (alcohol suppresses SWS quality despite initially deepening sleep through sedation); Magnesium L-Threonate at 1,500–2,000mg daily with evening dosing to support GABAergic SWS induction and sleep spindle density; Ashwagandha KSM-66 for cortisol management if stress is a factor; morning aerobic exercise for BDNF elevation and circadian timing reinforcement; and consistent sleep timing to anchor the circadian scheduling of SWS episodes. The combination of temperature optimization and alcohol avoidance produces the most immediate SWS improvements; MgT and consistent timing produce the most sustained architectural improvements over weeks.

What happens during REM sleep?

REM sleep is characterized by near-waking brain activity patterns, complete skeletal muscle atonia (preventing the physical enactment of dreams), rapid conjugate eye movements, and vivid narrative dreaming. Neurochemically, REM is dominated by acetylcholine and serotonin while norepinephrine and histamine are nearly absent — producing the loose associative thinking and reduced prefrontal inhibition that generate the creative dream narrative. During REM, four primary functions occur: emotional memory processing (replaying emotionally charged experiences in a low-norepinephrine environment that reduces emotional intensity while preserving memory content), creative integration (forming novel associations between distantly related memories through the relaxed prefrontal control), procedural and motor memory consolidation (transferring recently practiced physical and cognitive skills into automatic performance), and synaptic downscaling (pruning weak redundant connections to maintain signal-to-noise clarity in memory networks). REM sleep is concentrated in the second half of the night — the final 2 hours of an 8-hour sleep period contain a disproportionate share of the night’s total REM — making early wake times and short sleep disproportionately costly for REM-dependent functions.

Why do sleep trackers show different sleep stage data?

Consumer sleep trackers (Oura, Fitbit, Apple Watch, Whoop) estimate sleep stages from peripheral physiological signals — primarily heart rate variability, movement, skin temperature, and respiratory rate — rather than the direct EEG measurements used in clinical polysomnography. These peripheral signals correlate imperfectly with actual brain sleep stages, producing significant inaccuracies in stage-specific estimates compared to EEG gold standard. Research comparing consumer trackers to polysomnography has found reasonable accuracy for distinguishing sleep from wakefulness, but substantially lower accuracy for differentiating SWS from N2 and for accurately measuring REM duration. The practical implication is that consumer trackers are most useful for tracking trends within an individual over time — whether your SWS trend is improving or worsening in response to behavioral changes — rather than for accurate absolute stage measurements. Night-to-night variation in tracker data should not be over-interpreted; week-to-week trends are more meaningful and actionable.

Does sleep architecture change with age?

Yes — sleep architecture changes significantly and systematically with age, with the most consequential change being a dramatic reduction in slow wave sleep. SWS constitutes approximately 20% of total sleep time in young adults but declines to less than 5% in adults over 60, with the steepest decline occurring between the 30s and 50s. This SWS reduction produces age-associated reductions in growth hormone secretion, impaired glymphatic clearance of amyloid-beta and tau, and reduced declarative memory consolidation — all contributing to age-related cognitive decline independently of other aging factors. Sleep onset latency also increases with age, arousal frequency increases (producing more fragmented sleep), and the circadian clock becomes less robustly entrained, producing earlier sleep-wake timing and less stable circadian rhythms. The behavioral and supplementation interventions that optimize sleep architecture — particularly MgT for sleep spindle enhancement, consistent sleep timing, temperature optimization, and morning light exposure — are especially valuable for older adults because they specifically target the architectural elements that aging most compromises. Regular aerobic exercise is additionally particularly impactful for maintaining SWS in aging, with research showing that older adults who exercise regularly maintain significantly better SWS architecture than sedentary peers.

Sleep Architecture as the Map for Precision Sleep Optimization

Sleep architecture provides what most sleep advice lacks: specificity. Understanding that your 6-hour sleep is eliminating 60–70% of your REM tells you something entirely different from knowing that your bedroom is too warm for adequate SWS. Understanding that your evening alcohol is producing REM suppression and second-half fragmentation explains why 8 hours of alcohol-assisted sleep leaves you feeling worse than 7 hours without it. The architecture is the diagnostic framework that makes sleep optimization a precision practice rather than a collection of generic advice.

The actionable summary: protect SWS with temperature optimization, caffeine discipline, and MgT. Protect REM with adequate total sleep duration, alcohol avoidance, and stress management. Maintain both with consistent sleep timing and morning light. These interventions address the specific neurobiological mechanisms of each stage rather than sleep in the abstract — and produce correspondingly specific, reliable improvements in the functions each stage provides.

For the complete behavioral and supplementation sleep protocol, see the complete sleep guide. For the memory consolidation functions of SWS and REM in depth, see the sleep and memory guide. For the supplement details, see the Magnesium L-Threonate guide and Ashwagandha guide.

References

- Lüthi, A., & McCormick, D.A. (2013). Sleep spindles: Where they come from, what they do. Neuroscientist, 16(4), 391–398. PubMed

- Xie, L., et al. (2013). Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science, 342(6156), 373–377. PubMed

- Van Cauter, E., et al. (2000). Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep. JAMA, 284(7), 861–868. PubMed

- Wagner, U., et al. (2004). Sleep inspires insight. Nature, 427(6972), 352–355. PubMed

- Plihal, W., & Born, J. (1997). Effects of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9(4), 534–547. PubMed

- Ohayon, M.M., et al. (2004). Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters across the lifespan. Sleep, 27(7), 1255–1273. PubMed

- Ebrahim, I.O., et al. (2013). Alcohol and sleep I: Effects on normal sleep. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(4), 539–549. PubMed

- Drake, C., et al. (2013). Caffeine effects on sleep taken 0, 3, or 6 hours before going to bed. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 9(11), 1195–1200. PubMed

- Stickgold, R. (2005). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature, 437(7063), 1272–1278. PubMed

Tags: sleep architecture, sleep stages, slow wave sleep, REM sleep, NREM sleep, sleep spindles, sleep cycles, N3 deep sleep, sleep architecture disruption, how to get more deep sleep, REM sleep functions, sleep architecture aging, alcohol sleep architecture, caffeine sleep stages, sleep stage optimization

About Peter Benson

Peter Benson is a cognitive enhancement researcher and mindfulness coach with 18+ years of personal and professional experience in nootropics, neuroplasticity, and sleep optimization protocols. He has personally coached hundreds of individuals through integrated cognitive performance programs combining evidence-based sleep strategies with targeted supplementation. NeuroEdge Formula is his platform for sharing rigorous, safety-first cognitive enhancement guidance.