Sleep and Cognitive Performance: The Neuroscience of What Sleep Deprivation Does to Your Brain

Medical Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. If you are experiencing significant sleep difficulties affecting your cognitive performance or daily functioning, consult a qualified healthcare provider. Always consult a healthcare provider before beginning any supplement regimen. Individual responses vary.

If you could take a drug that improved attention, working memory, reaction time, emotional regulation, creative problem solving, and long-term memory retention — simultaneously — you would take it. That drug exists. It is called sleep. And the inverse is equally true: chronic mild sleep restriction produces cognitive impairments across every one of those domains simultaneously — impairments that accumulate progressively, that most people completely fail to perceive in themselves, and that no amount of motivation, caffeine, or effort can compensate for.

The neuroscience of sleep and cognitive performance is one of the most thoroughly researched areas in all of neuroscience — and the findings are unambiguous in a way that few areas of brain research achieve. Sleep deprivation is not merely uncomfortable. It produces specific, measurable neurobiological impairments at every level of cognitive function: cellular (LTP impairment), network (prefrontal connectivity disruption), and systems (memory consolidation failure). Understanding those mechanisms is what reveals both the cost of insufficient sleep and the specific cognitive benefits of optimizing it.

After 18+ years coaching individuals through cognitive optimization, the pattern I see consistently is this: people dramatically underestimate how much their cognitive performance is being limited by sleep and dramatically overestimate their ability to detect that limitation in themselves. The research supports both observations with disturbing precision. This guide covers the complete neuroscience — what sleep deprivation does to each domain of cognitive function, why you cannot accurately assess your own impairment, and how sleep optimization produces cognitive improvements that no other intervention matches.

The Cognitive Cost of Insufficient Sleep: Domain by Domain

Attention and Sustained Focus: The Most Visible Casualty

Sustained attention — the ability to maintain alert, focused processing over time — is the cognitive function most sensitive to sleep deprivation, and the first to show measurable impairment as sleep quantity or quality declines. The landmark Van Dongen study found that restricting sleep to 6 hours per night for 14 days produced sustained attention deficits equivalent to going 24 hours without sleep at all — while the subjects themselves rated their sleepiness as only slightly elevated and believed they were functioning adequately. This dissociation between objective performance and subjective assessment is one of the most dangerous findings in sleep science: sleep deprivation impairs the metacognitive accuracy required to recognize sleep deprivation’s effects.

The neurobiological mechanism is well-characterized: sleep deprivation reduces activity in the thalamo-cortical circuits responsible for sustaining alert wakefulness, particularly the noradrenergic and cholinergic arousal systems whose function degrades as adenosine accumulates beyond the threshold cleared by adequate sleep. The result is increased attentional lapses — brief (2–15 second) episodes of functional unresponsiveness that the person experiencing them typically does not notice — that accumulate in frequency across the day and produce the characteristic Swiss-cheese quality of attention in sleep-restricted individuals.

Working Memory and Executive Function: The PFC Under Siege

The prefrontal cortex — the neural substrate of working memory, executive control, planning, and inhibitory function — is disproportionately vulnerable to sleep deprivation compared to other brain regions. Research on sleep deprivation and prefrontal function found that PFC-dependent tasks — complex reasoning, planning, creative problem solving, impulse control, flexible cognitive updating — show greater impairment from sleep restriction than simple tasks requiring only basic sensory processing and response. This is the neuroscience of why sleep-deprived individuals make poor decisions while remaining confident in them: the very system responsible for evaluating decision quality is the most impaired.

Working memory capacity — the number of items the PFC can simultaneously maintain and manipulate — is directly reduced by sleep deprivation through catecholamine depletion. Dopamine and norepinephrine, which maintain the persistent neural activity of working memory representations in PFC, are depleted by insufficient sleep and require adequate slow-wave sleep for restoration. The working memory impairment from a single night of restricted sleep is the neurobiological equivalent of the PFC catecholamine depletion produced by chronic stress — and it accumulates across nights in ways that single nights of recovery sleep cannot fully reverse.

Memory Consolidation: Learning Without Sleeping Does Not Stick

The memory consolidation functions of sleep — detailed in the sleep and memory guide — represent perhaps the most direct and most consequential connection between sleep and cognitive performance. Information encoded during a day without subsequent adequate sleep is not merely weakly consolidated — it may be permanently impaired in ways that later sleep cannot reverse, because the hippocampal consolidation window for newly encoded memories is time-limited.

Research by Yoo and colleagues found that a single night of sleep deprivation reduced hippocampal encoding activity by approximately 40% during subsequent learning — meaning that sleep-deprived individuals encode new information with fundamentally less neural engagement, producing memory traces that are weaker before consolidation even begins. The compound effect on anyone engaged in serious learning is severe: not only is the consolidation of previous learning impaired by insufficient sleep, but the encoding of new learning the following day is also impaired — a double hit that makes the sleep-deprived student or professional’s situation progressively worse with each consecutive night of restriction.

Emotional Regulation: The Amygdala Unleashed

Sleep deprivation produces a characteristic emotional dysregulation profile — increased emotional reactivity, reduced frustration tolerance, impaired emotional nuance detection in others’ faces, and a shift toward negative emotional interpretation of ambiguous social cues. Research by Walker and colleagues found that sleep-deprived individuals showed 60% greater amygdala reactivity to emotionally provocative images than well-rested controls — with a simultaneous disruption of the prefrontal-amygdala connectivity that normally provides top-down emotional regulation. The sleep-deprived brain reacts more intensely to emotional stimuli while having reduced capacity to modulate that reaction — the neurobiological mechanism of why sleep-deprived individuals have shorter fuses, less empathy, and poorer interpersonal judgment.

The professional consequences are significant and underappreciated: leadership quality, negotiation performance, team communication, and long-term strategic decision-making are all PFC-dependent functions that the emotional dysregulation of sleep restriction directly impairs. The leader who “pushes through” on 6 hours of sleep is not a model of discipline — they are operating with measurably impaired judgment, reduced empathy, and increased emotional reactivity in exactly the interactions that most require the opposite.

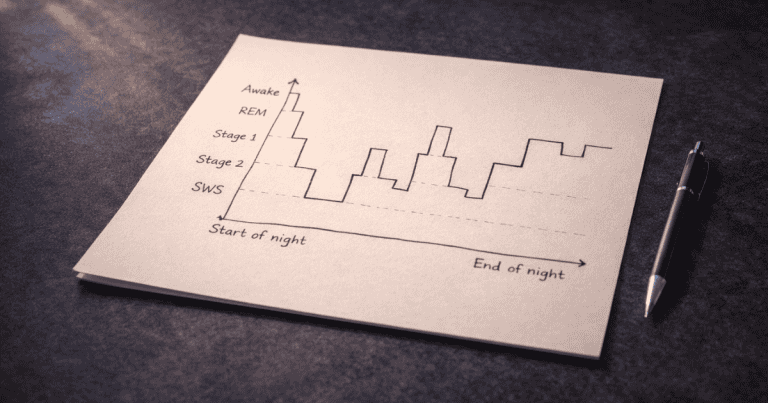

Creative Problem Solving: REM as the Insight Generator

Creative insight — the ability to find non-obvious solutions to complex problems, identify hidden patterns in data, and make unexpected connections between distantly related ideas — is among the most REM-dependent cognitive functions. The low-norepinephrine, high-acetylcholine neurochemical environment of REM sleep promotes the loose associative processing that generates genuine insight, while the truncated REM of sleep restriction eliminates this creative processing before it completes.

Research by Wagner and colleagues found that REM-rich sleep tripled the likelihood of discovering a hidden mathematical rule in a number sequence task — participants who slept showed insight that was largely absent in those kept awake. For professionals whose value depends on creative problem solving, strategic insight, or novel synthesis of complex information, REM sleep is not a luxury — it is the neurobiological mechanism through which those capabilities are generated.

Reaction Time and Physical Performance

Psychomotor vigilance — simple reaction time — shows progressive and linear degradation with sleep restriction that mirrors the subjective sleepiness curve but extends further and declines faster. Van Dongen’s research documented that 6-hour sleepers showed continuous, unremitting reaction time degradation across 14 days — not plateauing or adapting, as subjects believed — reaching performance levels that would be considered dangerously impaired if produced by alcohol. Physical performance across nearly every athletic metric — sprint speed, strength, accuracy, endurance, injury risk — shows significant impairment from sleep restriction and significant improvement from sleep extension, making sleep the most consistently performance-enhancing intervention in sports science.

Free Download

Get the 7-Day Brain Optimization Protocol

The evidence-based diet, sleep, and supplement framework for your first week of cognitive enhancement — completely free.

Join 2,000+ readers optimizing their cognitive performance. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Most Dangerous Finding: Why You Cannot Detect Your Own Impairment

The most practically consequential finding in sleep deprivation research is not the magnitude of the cognitive impairments — it is the consistent finding that sleep-deprived individuals dramatically underestimate those impairments in themselves. This is not a matter of denial or willpower — it is a specific neurobiological consequence of the same PFC impairment that sleep restriction produces.

The prefrontal cortex is not only the seat of executive function — it is also the neural substrate of metacognition, the ability to accurately assess one’s own cognitive state and performance quality. When the PFC is impaired by sleep restriction, the system responsible for detecting that impairment is itself impaired. Van Dongen’s research documented that across 14 days of 6-hour sleep restriction, subjects’ objective performance on attention and reaction time tasks continued to deteriorate daily while their subjective ratings of sleepiness plateaued after 3–4 days — they adapted to feeling mildly sleepy while their actual performance degraded continuously toward severe impairment.

The cultural normalization of sleep restriction compounds this further. “I only need 6 hours” is one of the most common claims I hear — and one of the most reliably associated with the performance profile of someone who is chronically impaired and cannot accurately detect it. The research shows that true short-sleepers — individuals with the rare genetic variants that allow adequate cognitive function on less than 7 hours — constitute less than 3% of the population. The other 97% claiming to function well on 6 hours are, by the evidence, mistaken about their own performance in the same systematic way that Van Dongen’s subjects were: feeling okay while testing like someone who has been awake for 24 hours.

The Cognitive Dividend of Sleep Optimization

The inverse of the deprivation research is equally compelling: sleep optimization — extending duration toward 8 hours, improving SWS depth and REM quality through the behavioral and supplementation protocols in this hub — produces cognitive improvements that no other single intervention matches for breadth or magnitude.

Sleep Extension Research: What Happens When You Actually Sleep Enough

Research on sleep extension in athletes by Mah and colleagues found that extending sleep toward 10 hours for 5–7 weeks produced dramatic improvements across multiple performance domains: reaction time improved by 19%, sprint speed improved significantly, shooting accuracy improved by 9%, and subjective mood, vigor, and alertness all improved substantially. These athletes were not previously sleep-deprived by their own assessment — they were functioning athletes extending from their habitual ~6.5–7 hours. The improvements represent the recovery of performance capacity that chronic mild restriction had eliminated without the athletes recognizing the deficit.

For cognitive rather than athletic performance, the parallel findings are consistent: individuals who extend sleep from habitual short sleep to 8+ hours show improvements in working memory, sustained attention, creative problem solving, and emotional regulation that mirror the impairments documented in the deprivation research — the same coin, both faces.

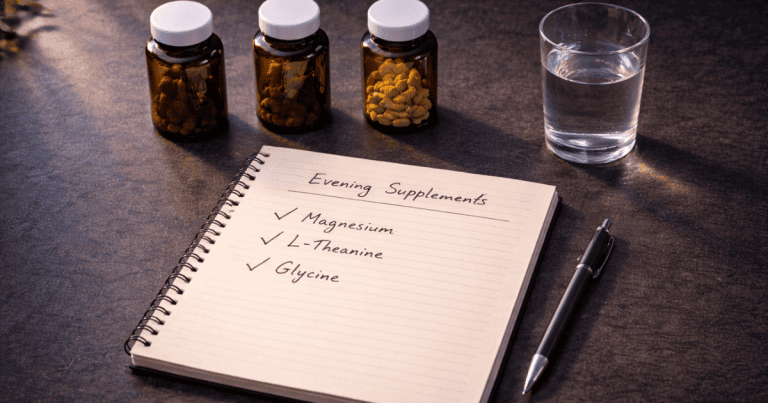

The Supplement Stack That Maximizes Sleep’s Cognitive Dividend

The supplementation protocols across this hub are designed to amplify the cognitive dividend of adequate sleep by improving the quality of the sleep obtained. Magnesium L-Threonate’s sleep spindle enhancement directly improves N2 and SWS quality — the consolidation mechanisms that transfer encoded memories into durable long-term storage. Ashwagandha’s cortisol management protects SWS depth and REM duration from the stress-driven fragmentation that degrades sleep quality even when duration is adequate. L-theanine’s pre-sleep alpha-wave promotion reduces the sleep onset latency that, when prolonged, reduces total sleep time and shifts the architecture toward lighter stages.

The combined effect — adequate duration, improved SWS depth, protected REM cycling, reduced sleep onset latency — produces a sleep quality that the behavioral interventions alone cannot achieve for individuals with significant stress, magnesium insufficiency, or chronic cortisol elevation. And the cognitive performance benefits of that quality sleep compound with the behavioral and supplementation cognitive enhancement strategies throughout the Focus and Memory hubs into a multiplied effect that no single-domain optimization produces in isolation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sleep and Cognitive Performance

How does lack of sleep affect cognitive performance?

Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive performance through three simultaneous mechanisms operating at different levels. At the cellular level, insufficient slow-wave sleep impairs long-term potentiation — the synaptic strengthening mechanism that underlies memory formation — and reduces the glymphatic clearance of metabolic waste products including amyloid-beta. At the network level, sleep deprivation reduces prefrontal cortex activity and PFC-amygdala connectivity, impairing working memory, executive function, impulse control, and emotional regulation while increasing amygdala reactivity. At the systems level, insufficient REM sleep eliminates the hippocampal-cortical memory consolidation, creative integration, and emotional processing that sleep provides and wakefulness cannot replicate. The practical consequences span every domain of cognitive performance: sustained attention degrades (with attentional lapses accumulating), working memory capacity shrinks, new learning consolidates poorly, decision quality drops, emotional reactivity increases, and creative insight becomes unavailable. Critically, these impairments accumulate across consecutive nights of restriction in ways that single nights of recovery cannot fully reverse, and they are consistently underestimated by the impaired individuals themselves.

Can you catch up on sleep debt over the weekend?

Weekend sleep extension partially but not fully reverses the cognitive impairments of weekday sleep restriction — and introduces new impairments through social jetlag. Research on sleep debt recovery found that while some acute cognitive impairments from the prior week improve after a weekend of extended sleep, the metabolic consequences (insulin sensitivity, inflammatory markers, hormonal dysregulation) persist beyond the cognitive improvements, and the circadian disruption from sleeping dramatically later on weekends delays sleep onset on Sunday night — producing the “Monday morning effect” of impaired cognitive performance from circadian misalignment. The most important finding is that consistent adequate sleep throughout the week produces dramatically better cognitive outcomes than alternating restriction and recovery — the brain performs best with stable, adequate sleep every night, not compensatory binges after accumulated deficit. The practical implication: weekend sleep-ins are not an effective substitute for consistent 7–9 hour sleep but are still preferable to extending the restriction into the weekend when the only alternative is further restriction.

How much does sleep deprivation affect IQ and cognitive performance scores?

Sleep deprivation’s effects on standardized cognitive performance are substantial. Research shows that 24 hours without sleep produces cognitive performance equivalent to a blood alcohol concentration of 0.10% — above the legal driving limit in most jurisdictions. Seventeen hours of wakefulness (a normal late work day) produces performance equivalent to 0.05% blood alcohol. For chronic restriction rather than total deprivation, Van Dongen’s research found that 14 days of 6-hour sleep produced performance deficits on sustained attention and processing speed that were statistically equivalent to 24-hour total deprivation — while subjects remained largely unaware of the severity of their impairment. On complex cognitive tasks requiring PFC function — reasoning, creative problem solving, flexible updating — the impairments are more severe than on simple psychomotor tasks, because the prefrontal cortex is disproportionately vulnerable to sleep loss. Expressing this as IQ points: research has estimated that acute total sleep deprivation reduces effective IQ scores by approximately 5–15 points on tasks requiring fluid intelligence and executive function — a significant reduction that would be immediately apparent on a test but is typically invisible to the impaired individual in daily performance.

What cognitive functions recover fastest after better sleep?

Different cognitive functions show different recovery timelines from sleep optimization, reflecting the different biological mechanisms through which sleep deprivation impairs them. Mood and subjective alertness recover fastest — often within 1–2 nights of adequate sleep — because they reflect acute adenosine and catecholamine normalization rather than structural impairment. Sustained attention and reaction time recover significantly within 1–3 nights of adequate sleep. Working memory and executive function show more gradual recovery — 5–7 days of adequate sleep for substantial recovery from extended mild restriction. Emotional regulation and interpersonal performance recover in parallel with sustained attention, within 1–3 nights. Memory consolidation for information encoded during the sleep-deprived period does not fully recover — the consolidation window for those memories passed without adequate sleep. The cognitive functions that are most impaired by chronic restriction and most slowest to recover are those requiring sustained neuroplasticity: the hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic density that adequate sleep supports and sleep restriction suppresses over time take weeks to months of adequate sleep to restore to their optimum. This is why the sleep optimization protocol emphasizes consistency over weeks rather than recovery on isolated nights.

Does napping improve cognitive performance?

Yes — strategic napping produces measurable cognitive performance improvements, particularly for individuals with sleep debt or those facing cognitively demanding afternoon work. A 20-minute nap (short enough to avoid SWS entry and the grogginess of deep sleep inertia) produces improvements in alertness, reaction time, and sustained attention lasting 2–3 hours — without significantly reducing nighttime sleep pressure when taken before 2pm. A 90-minute nap containing both SWS and REM produces more comprehensive cognitive restoration, improving declarative memory, emotional processing, and creative performance in addition to alertness — but requires careful timing (ending before 3pm) to avoid disrupting nighttime sleep onset. Research on NASA pilots found that a 26-minute nap improved performance by 34% and alertness by 100% — the foundation of the “NASA nap” recommendation. The optimal napping protocol for cognitive performance depends on the primary goal: a 20-minute nap for acute alertness and reaction time, a 90-minute nap for memory consolidation benefit and more comprehensive restoration. Neither replaces the full overnight architecture of adequate nighttime sleep but both meaningfully mitigate the cognitive cost of unavoidable acute sleep restriction.

The Honest Arithmetic of Sleep and Cognitive Performance

The research makes a case that most high performers do not want to hear: the extra hours of work gained by sleeping 6 hours instead of 8 are hours of severely impaired work — hours that produce a fraction of the output, decision quality, and creative insight that the same person would produce with adequate sleep. The sleep-deprived professional working 16 hours outproduces the well-rested professional working 10 hours only in hours billed, not in value created. The arithmetic of sleep-driven performance is not the one most hustle culture narratives assume.

After 18+ years observing this pattern, the shift I see most consistently in the individuals whose cognitive performance improves most dramatically is not a new supplement or a more sophisticated protocol — it is the decision to treat sleep as the highest-priority cognitive performance intervention, not the variable that gets compressed when other demands increase. Everything else in this site is more effective on top of that decision.

For the complete sleep optimization protocol, see the complete sleep guide. For the memory consolidation mechanisms in depth, see the sleep and memory guide. For the nootropic stack that maximizes the cognitive dividend of adequate sleep, see the sleep supplements guide and the Nootropics hub.

References

- Van Dongen, H.P., et al. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep, 26(2), 117–126. PubMed

- Harrison, Y., & Horne, J.A. (2000). The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making. Journal of Sleep Research, 9(1), 49–58. PubMed

- Yoo, S.S., et al. (2007). A deficit in the ability to form new human memories without sleep. Nature Neuroscience, 10(3), 385–392. PubMed

- Walker, M.P., & van der Helm, E. (2009). Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 731–748. PubMed

- Wagner, U., et al. (2004). Sleep inspires insight. Nature, 427(6972), 352–355. PubMed

- Mah, C.D., et al. (2011). The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players. Sleep, 34(7), 943–950. PubMed

- Stickgold, R. (2005). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature, 437(7063), 1272–1278. PubMed

- Xie, L., et al. (2013). Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science, 342(6156), 373–377. PubMed

- Dinges, D.F., et al. (1997). Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per night. Sleep, 20(4), 267–277. PubMed

Tags: sleep and cognitive performance, sleep deprivation effects, sleep and brain function, sleep deprivation working memory, sleep and attention, sleep deprivation PFC, sleep and creativity, REM sleep cognitive performance, sleep debt cognitive impairment, Van Dongen sleep study, sleep and decision making, sleep deprivation emotional regulation, sleep extension performance, sleep and memory consolidation, chronic sleep restriction

About Peter Benson

Peter Benson is a cognitive enhancement researcher and mindfulness coach with 18+ years of personal and professional experience in nootropics, neuroplasticity, and sleep optimization protocols. He has personally coached hundreds of individuals through integrated cognitive performance programs combining evidence-based sleep strategies with targeted supplementation. NeuroEdge Formula is his platform for sharing rigorous, safety-first cognitive enhancement guidance.