Working Memory: What It Is and How to Expand It

Medical Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before beginning any supplement regimen or making significant changes to your health protocols. Individual responses vary. This guide reflects published research and 18+ years of personal experience and does not substitute for professional medical evaluation.

Working memory is the cognitive workspace in which thinking happens. It is where you hold the beginning of a sentence while constructing its end, where you maintain a chain of reasoning while applying each step, where you keep track of multiple variables while solving a complex problem. Unlike long-term memory — which stores information indefinitely — working memory is temporary, limited in capacity, and directly dependent on the biological state of the prefrontal cortex at any given moment.

Working memory capacity is one of the strongest predictors of academic achievement, professional performance, and fluid intelligence ever identified in cognitive psychology. Research on working memory and general cognitive ability found that individual differences in working memory capacity explain a substantial portion of the variance in reading comprehension, mathematical reasoning, problem-solving ability, and fluid intelligence — more predictive than IQ scores alone for many real-world performance outcomes. It is also one of the most frequently overlooked variables in cognitive performance optimization, with most attention directed at long-term memory strategies while the cognitive workspace that processes and applies that memory is left unaddressed.

This guide covers the complete neuroscience of working memory — what it actually is at the neurological level, why it is limited, what determines its capacity in any given individual, and the full evidence-based protocol for expanding and optimizing it. It connects the Focus hub’s prefrontal cortex optimization strategies to the Memory hub’s supplementation protocols, establishing working memory as the neurological bridge between focused attention and effective long-term learning. It builds on the complete memory guide and connects to the focus guide, the learning guide, and the supplementation strategies throughout the Nootropics hub.

What Working Memory Actually Is: The Neurological Reality

Working memory is frequently described as a mental scratchpad — a useful analogy that captures its temporary nature but misses its most important neurological characteristics. Working memory is not a storage buffer — it is an active maintenance process, requiring constant neural activity to keep information accessible and preventing it from fading into the background noise of irrelevant neural activity.

The Baddeley Model: Components of Working Memory

The most influential model of working memory — developed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch — describes it as a multi-component system with four interacting subsystems. Understanding these subsystems explains why certain tasks tax working memory more than others and why specific interventions target specific components.

The central executive is the attentional control system — the component that directs attention, coordinates the other subsystems, switches between tasks, inhibits irrelevant information, and updates working memory content as task demands change. The central executive is implemented primarily in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex — the same PFC regions that focus and executive function depend on. Central executive capacity is what people typically mean when they refer to “working memory capacity” — it determines how many things can be actively processed simultaneously and how effectively irrelevant information can be suppressed.

The phonological loop stores and rehearses verbal information — the inner voice that repeats information to prevent it from fading. When you hold a phone number in mind by silently repeating it, you are using the phonological loop. It is implemented in left hemisphere perisylvian language regions and has a capacity of approximately 2 seconds of speech — the origin of the famous “magical number seven” (which is actually the number of chunks that can be rehearsed in approximately 2 seconds of inner speech).

The visuospatial sketchpad maintains visual and spatial information — the mental imagery system that holds the layout of a room, the shape of an object, or the position of pieces on a chess board. It is implemented in right hemisphere parietal and occipital regions and operates largely independently of the phonological loop — allowing verbal and visual information to be maintained simultaneously without interference.

The episodic buffer integrates information from the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and long-term memory into coherent episodes — binding the different elements of a working memory representation into a unified conscious experience. It is the component that allows working memory to draw on long-term memory knowledge while maintaining current task information.

The Neural Implementation: Persistent Activity in the PFC

Working memory is neurologically implemented through persistent neural activity — neurons in the prefrontal cortex that continue firing after a stimulus is removed, maintaining its representation in an active state against the constant pressure of irrelevant neural noise. Research on prefrontal persistent activity and working memory found that this sustained firing requires continuous dopamine and norepinephrine modulation — without adequate catecholamine tone, PFC neurons cannot maintain the sustained activity that working memory requires, and representations fade into background noise. This is the direct neurological mechanism explaining why working memory performance is so sensitive to PFC neurochemical state — and why stress, sleep deprivation, and catecholamine deficits so reliably impair working memory capacity.

Why Working Memory Is Limited

Working memory capacity is limited not by storage space — in the way a hard drive has limited storage — but by the neural resources required to maintain active representations against interference. Each actively maintained representation requires sustained PFC firing that competes for the same catecholamine-dependent neural resources as every other active representation. As the number of simultaneously maintained representations increases, each representation becomes more vulnerable to interference and displacement. Research on working memory capacity limits established that the typical limit is 3–4 chunks of information — far less than the “magical number seven” originally proposed — with individual variation ranging from 2 to 6 chunks depending on PFC efficiency, catecholamine availability, and the degree to which information has been chunked through expertise.

Chunking — the process of grouping multiple elements into a single meaningful unit through long-term memory knowledge — is the primary mechanism by which expertise effectively expands working memory capacity. A chess grandmaster’s working memory is not larger than a novice’s — but their deep long-term memory knowledge allows them to perceive entire board configurations as single chunks rather than dozens of individual piece positions. The result is that more complex information fits within the same 3–4 chunk capacity limit.

What Determines Working Memory Capacity: The Modifiable Variables

Working memory capacity is not fixed. It varies significantly across individuals and within the same individual across different biological states — and many of the variables that determine it are directly modifiable through the behavioral and supplementation protocols described throughout this site.

Prefrontal Catecholamine Tone: The Primary Neurochemical Determinant

The most important single determinant of working memory capacity in any given moment is dopamine and norepinephrine availability in the PFC. Research on catecholamines and working memory established that both dopamine and norepinephrine exert inverted-U dose-response effects on PFC working memory performance — too little produces insufficient signal for sustained activity; too much produces excessive noise that disrupts the signal-to-noise ratio required for precise representation maintenance. The optimal catecholamine state for working memory — moderate, stable dopamine and norepinephrine tone — is precisely what the morning protocol, caffeine and L-theanine supplementation, and stress management strategies throughout this site are designed to maintain.

Acute stressors that spike cortisol, sleep deprivation that depletes catecholamine reserves, and chronic stress that chronically elevates glucocorticoids all shift PFC catecholamine tone away from the optimal working memory range — producing measurable working memory impairments that are not character flaws or lack of effort but direct neurochemical consequences of biological state. Conversely, the morning exercise, caffeine and L-theanine timing, and stress management protocols described in the morning routine guide reliably shift PFC catecholamine tone toward the optimal range — producing working memory improvements that are as neurobiologically real as the impairments they reverse.

Sleep: Overnight Restoration of Working Memory Capacity

Research on sleep deprivation and working memory found that even moderate sleep restriction — 6 hours per night for 14 days — produces working memory performance deficits equivalent to two nights of total sleep deprivation, and that individuals are remarkably poor at subjectively assessing their own working memory impairment under these conditions. The PFC catecholamine systems that working memory depends on are restored primarily during sleep — making consistent adequate sleep the single most impactful working memory intervention available, before any supplement or behavioral strategy is considered.

Smartphone Proximity: The Hidden Working Memory Tax

The Ward et al. research referenced throughout the Focus hub is equally relevant for working memory: the mere presence of a smartphone on the desk — silent, face-down, not in use — reduces available working memory capacity through the cognitive resources allocated to suppressing the impulse to check it. For working memory specifically, this represents a continuous background tax on the PFC resources that working memory maintenance requires — reducing the effective capacity available for the actual task regardless of whether the phone is consciously attended to. Physical phone removal from the work environment is a working memory intervention, not merely a distraction management preference.

Free Download

Get the 7-Day Brain Optimization Protocol

The evidence-based diet, sleep, and supplement framework for your first week of cognitive enhancement — completely free.

Join 2,000+ readers optimizing their cognitive performance. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Complete Working Memory Optimization Protocol

Working memory optimization operates across three complementary layers: neurochemical optimization that addresses the biological substrate of PFC persistent activity; behavioral strategies that reduce unnecessary working memory load and train the attentional control component; and supplementation that directly supports PFC catecholamine signaling and the structural neuroplasticity of PFC circuits.

Layer 1 — Neurochemical Optimization: The Biological Foundation

Caffeine and L-theanine (the acute working memory stack): The 1:2 ratio caffeine and L-theanine combination directly addresses the PFC catecholamine requirements of working memory. Caffeine’s adenosine blockade increases dopamine receptor availability and elevates norepinephrine — shifting PFC catecholamine tone toward the optimal working memory range. L-theanine moderates the anxiety that pure caffeine can produce at higher doses, preventing the cortisol elevation that would shift catecholamine tone past the optimal range into the impaired-high end of the inverted-U. The combination produces reliable acute working memory improvements within 30–60 minutes of ingestion, documented across multiple randomized controlled trials. Timing at 60–90 minutes post-waking — after the cortisol awakening response has peaked naturally — maximizes the effectiveness of the caffeine-norepinephrine optimization.

Morning exercise (the catecholamine primer): Twenty to thirty minutes of moderate aerobic exercise before the first cognitive work session elevates dopamine, norepinephrine, and BDNF — priming PFC catecholamine tone for the working memory demands of the morning deep work session. The post-exercise catecholamine elevation window of 1–2 hours represents the day’s peak working memory performance window for most individuals, making exercise timing relative to cognitive work one of the highest-leverage performance optimizations available at no financial cost.

Sleep (the non-negotiable restoration): Given that sleep deprivation produces working memory deficits equivalent to two nights of total sleep deprivation at 6 hours per night over 14 days, sleep quality and duration are the primary working memory interventions — before any supplement or behavioral strategy. Magnesium L-Threonate at 1,500–2,000mg daily improves sleep quality through NMDA receptor optimization and GABAergic modulation — producing both direct working memory benefits through synaptic density improvements and indirect benefits through the enhanced PFC catecholamine restoration that higher-quality sleep produces.

Layer 2 — Cognitive Load Management: Freeing Working Memory Through External Systems

Working memory capacity cannot be increased beyond its neurobiological limits by sheer effort — but its effective functional capacity can be dramatically expanded by reducing the cognitive load imposed by tasks that do not require working memory to hold. The most impactful working memory expansion strategies are therefore not training exercises but cognitive load management systems that offload information from working memory to external systems — freeing the limited PFC resource for the tasks that genuinely require it.

The capture system (GTD-style externalisation): Every open loop in working memory — every task not yet completed, every commitment not yet recorded, every piece of information not yet processed — consumes working memory resources to maintain. A reliable external capture system (a trusted task list, calendar, and reference system) eliminates the need to maintain these items in working memory, freeing PFC resources for the current task. David Allen’s Getting Things Done methodology, stripped of its more elaborate elements, is essentially a working memory management system — and its effectiveness is neurobiologically grounded in exactly this mechanism.

Writing before thinking: Externalising information to paper or a screen before attempting to process it reduces the working memory load of the processing task by offloading representation maintenance to the external medium. Complex reasoning, planning, and problem-solving performed on paper consistently outperforms the same tasks performed entirely in working memory — not because writing is cognitively superior to thinking, but because it frees working memory from maintenance duties and allows it to focus entirely on processing.

Chunking through expertise development: As established above, expertise converts multiple working memory items into single chunks through long-term memory knowledge — effectively multiplying functional working memory capacity within a domain. Deliberate practice that builds genuine domain expertise is therefore simultaneously a long-term memory strategy and a working memory expansion strategy. The spaced repetition system from the spaced repetition guide is one of the most efficient methods for building the long-term memory knowledge base that enables expert-level chunking.

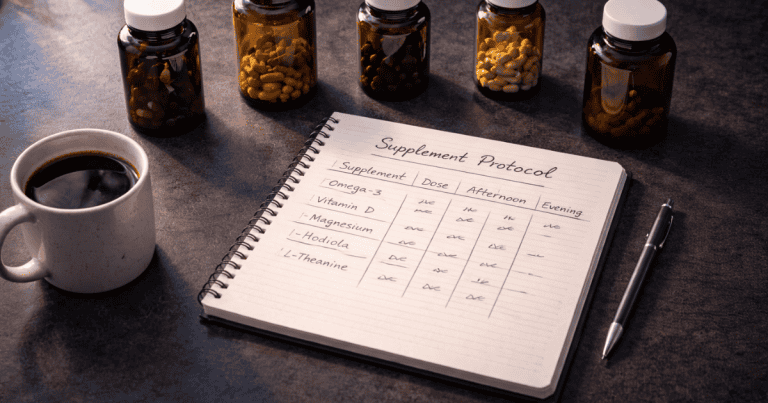

Layer 3 — Supplementation for PFC Structural Development

Alpha-GPC (cholinergic working memory support): Alpha-GPC at 300–600mg provides the acetylcholine precursor that directly supports the cholinergic modulation of PFC working memory circuits. Acetylcholine in the PFC enhances the signal-to-noise ratio of working memory representations — making actively maintained items more distinct from background neural noise and reducing their susceptibility to interference. Alpha-GPC’s acute acetylcholine elevation produces working memory improvements within the same session; its longer-term cholinergic support builds the acetylcholine synthetic capacity that sustains working memory performance across the day.

Lion’s Mane (PFC structural neuroplasticity): Lion’s Mane at 500–1,000mg drives NGF production and the myelination of PFC-subcortical circuits — directly building the structural neuroplasticity of the networks that implement working memory. Research on Lion’s Mane and cognitive function found improvements in processing speed and working memory tasks after 8–16 weeks of consistent supplementation — consistent with the NGF-driven myelination timeline that structural working memory improvement requires.

Bacopa Monnieri (cholinergic and antioxidant PFC support): Bacopa’s combination of cholinergic enhancement, dendritic branching promotion, and antioxidant protection of PFC neurons provides complementary structural support to Lion’s Mane’s NGF pathway — building working memory capacity through two independent neuroplasticity mechanisms simultaneously over the 8–12 week supplementation timeline.

Rhodiola Rosea (stress-resilient working memory): Rhodiola’s cortisol-modulating and monoamine-preserving effects are particularly relevant for working memory because cortisol’s impairment of PFC catecholamine signaling is the primary acute mechanism through which stress impairs working memory. Rhodiola before demanding cognitive sessions maintains the PFC dopamine-norepinephrine balance that working memory requires under conditions that would otherwise deplete it — producing stress-resilient working memory performance rather than the characteristic working memory degradation that unmanaged stress produces.

Layer 4 — Working Memory Training: What the Evidence Actually Shows

Working memory training — the use of adaptive cognitive exercises to directly expand working memory capacity — has been one of the most studied and most debated topics in cognitive psychology over the past two decades. The current evidence is more nuanced than either its early enthusiastic proponents or its subsequent skeptical critics suggested.

Meta-analyses of working memory training research found that adaptive working memory training produces reliable improvements on trained tasks — demonstrating that working memory performance on the specific exercises practiced can be improved. The more important question is near transfer — whether improvements on trained tasks generalize to untrained working memory tasks — and far transfer — whether they improve real-world cognitive performance measures like fluid intelligence and academic achievement. The evidence for far transfer is weaker and more inconsistent than early studies suggested, with the most robust conclusion being that working memory training improves working memory performance most reliably on tasks similar to those trained.

The practical implication is that working memory training through cognitively demanding work in one’s actual domain of expertise — writing, programming, analysis, design — produces more meaningful working memory development than abstract training games, because the domain-specific chunking and PFC engagement that develops through real work is directly applicable to real performance. Combined with the neurochemical optimization and supplementation protocols above, consistent engagement with cognitively demanding domain work is the most practically effective working memory development strategy available.

Frequently Asked Questions About Working Memory

What is working memory and how is it different from regular memory?

Working memory is the temporary active maintenance of information for immediate cognitive processing — the cognitive workspace where thinking occurs. It holds information in an active state while it is being manipulated, combined with other information, or used to guide behavior. Unlike long-term memory — which stores information indefinitely in distributed neural networks — working memory is temporary (lasting seconds to minutes without rehearsal), severely limited in capacity (approximately 3–4 chunks for most people), and directly dependent on sustained neural activity in the prefrontal cortex rather than on stable synaptic connections. The practical difference is experiential: long-term memory is what you know; working memory is what you are currently thinking about. Working memory capacity determines how complex a reasoning chain you can maintain, how many variables you can simultaneously consider in a problem, and how effectively you can connect new information to existing knowledge while learning — making it one of the strongest predictors of cognitive performance across virtually every domain.

Can working memory be improved?

Working memory can be improved through two complementary approaches. First, optimizing the neurobiological conditions that determine working memory capacity in any given moment — PFC catecholamine tone through exercise, caffeine and L-theanine timing, stress management, and sleep quality. These interventions produce reliable acute and sustained improvements in working memory performance by shifting the PFC neurochemical environment toward the optimal dopamine-norepinephrine balance that PFC persistent activity requires. Second, building the long-term memory knowledge that enables expert chunking — progressively grouping more information into fewer working memory items through domain expertise — effectively expands functional working memory capacity within a domain. The structural neuroplasticity compounds (Lion’s Mane, Bacopa, Alpha-GPC) build the PFC circuit architecture that raises the structural ceiling for both approaches over the 8–12 week supplementation timeline. Cognitive load management strategies — externalizing information to reliable systems and writing before processing — expand the effective functional capacity of working memory without changing its neurobiological limits.

Why does stress reduce working memory capacity?

Stress impairs working memory through two direct neurobiological mechanisms. First, cortisol — the primary stress hormone — impairs PFC catecholamine signaling by reducing dopamine and norepinephrine receptor sensitivity and increasing their reuptake, shifting PFC neurochemistry away from the optimal working memory range. Working memory requires precise, moderate dopamine and norepinephrine tone in the PFC for the sustained neural firing that maintains active representations; cortisol disrupts this balance and makes it impossible for PFC neurons to maintain representations against background noise as effectively. Second, the rumination and threat-monitoring that accompany stress actively consume working memory resources — the cognitive rehearsal of worries, the monitoring of the environment for threat, and the intrusion of stress-related thoughts all occupy working memory slots that would otherwise be available for the task at hand. Effective stress management — through Ashwagandha, Rhodiola, mindfulness practice, and adequate sleep — addresses both mechanisms simultaneously, protecting working memory capacity from the most common biological threat it faces in daily life.

Do brain training games improve working memory?

Brain training games reliably improve performance on the specific tasks they train — but the evidence for transfer to untrained working memory tasks and real-world cognitive performance is weaker and more inconsistent. Meta-analyses of working memory training research find reliable near-transfer effects (improvements on tasks similar to trained tasks) but inconsistent far-transfer effects (improvements on general fluid intelligence or academic performance measures). The most productive interpretation is that working memory training improves working memory performance most reliably in contexts similar to the training context — which makes domain-specific cognitive work (writing, programming, analysis, complex problem-solving in one’s actual domain) more practically valuable for working memory development than abstract training games, because domain-specific training produces chunking and PFC engagement directly applicable to the real-world performance it is meant to support. For individuals seeking maximum working memory improvement, the neurochemical optimization and structural supplementation protocols produce more reliable broad working memory benefits than any currently available training software.

How does sleep deprivation affect working memory?

Sleep deprivation impairs working memory through direct PFC catecholamine depletion — the overnight restoration of the dopamine and norepinephrine systems that PFC persistent activity requires is incomplete under sleep restriction, leaving working memory operating with insufficient neurochemical support. Research has found that six hours of sleep per night for 14 days produces working memory deficits equivalent to two consecutive nights of total sleep deprivation — and critically, that people severely underestimate their own working memory impairment under these conditions, rating their performance as near-normal while objective measurements show profound deficits. The progressive nature of sleep debt accumulation means that chronic mild sleep restriction — the norm for most working adults — produces chronic working memory impairment that is neurobiologically invisible to the person experiencing it. No supplement or behavioral strategy fully compensates for this impairment; consistent 7–9 hours of sleep remains the non-negotiable foundation of working memory performance before any optimization above baseline is possible.

Working Memory as the Bridge Between Focus and Learning

Working memory sits at the intersection of every cognitive performance domain covered throughout NeuroEdge Formula. It is the mechanism through which focused attention converts incoming information into encoded memories. It is the workspace in which retrieved long-term memories are applied to current problems. It is the cognitive substrate that determines the complexity of reasoning chains that can be maintained, the number of variables that can be simultaneously considered, and the effectiveness with which new knowledge is integrated with existing understanding.

Optimizing working memory therefore amplifies every other cognitive performance strategy simultaneously: better working memory makes deep work more productive, makes learning more efficient, makes problem-solving more effective, and makes the cognitive demands of high-performance professional work more manageable. The complete protocol — neurochemical optimization, cognitive load management, structural supplementation, and expert chunking through domain expertise — addresses every modifiable variable that determines working memory performance.

For the focus and PFC optimization strategies that share the same neurobiological substrate as working memory, see the complete focus guide. For the learning strategies that are most effectively implemented with optimized working memory, see the learning guide and spaced repetition guide. For the supplementation stack details, see Alpha-GPC, Lion’s Mane, Bacopa, and Rhodiola in the Nootropics hub.

References

- Engle, R.W. (2002). Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 19–23. PubMed

- Wang, M., et al. (2011). Neuronal basis of age-related working memory decline. Nature, 476(7359), 210–213. PubMed

- Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87–114. PubMed

- Arnsten, A.F., & Goldman-Rakic, P.S. (2005). Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function. Cerebral Cortex, 15(S1), i1–i20. PubMed

- Van Dongen, H.P., et al. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions. Sleep, 26(2), 117–126. PubMed

- Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 49(2), 270–291. PubMed

- Ward, A.F., et al. (2017). Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140–154. PubMed

- Haskell, C.F., et al. (2008). The effects of L-theanine, caffeine and their combination on cognition and mood. Biological Psychology, 77(2), 113–122. PubMed

- Arnsten, A.F. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. PubMed

Tags: working memory, working memory capacity, how to improve working memory, working memory neuroscience, prefrontal cortex working memory, working memory and intelligence, working memory training, cognitive load working memory, chunking working memory, catecholamines working memory, stress working memory, sleep working memory, Alpha-GPC working memory, working memory supplements, Baddeley working memory model

About Peter Benson

Peter Benson is a cognitive enhancement researcher and mindfulness coach with 18+ years of personal and professional experience in nootropics, neuroplasticity, and attention optimization protocols. He has personally coached hundreds of individuals through integrated cognitive improvement programs combining evidence-based learning strategies with targeted supplementation. NeuroEdge Formula is his platform for sharing rigorous, safety-first cognitive enhancement guidance.